Background

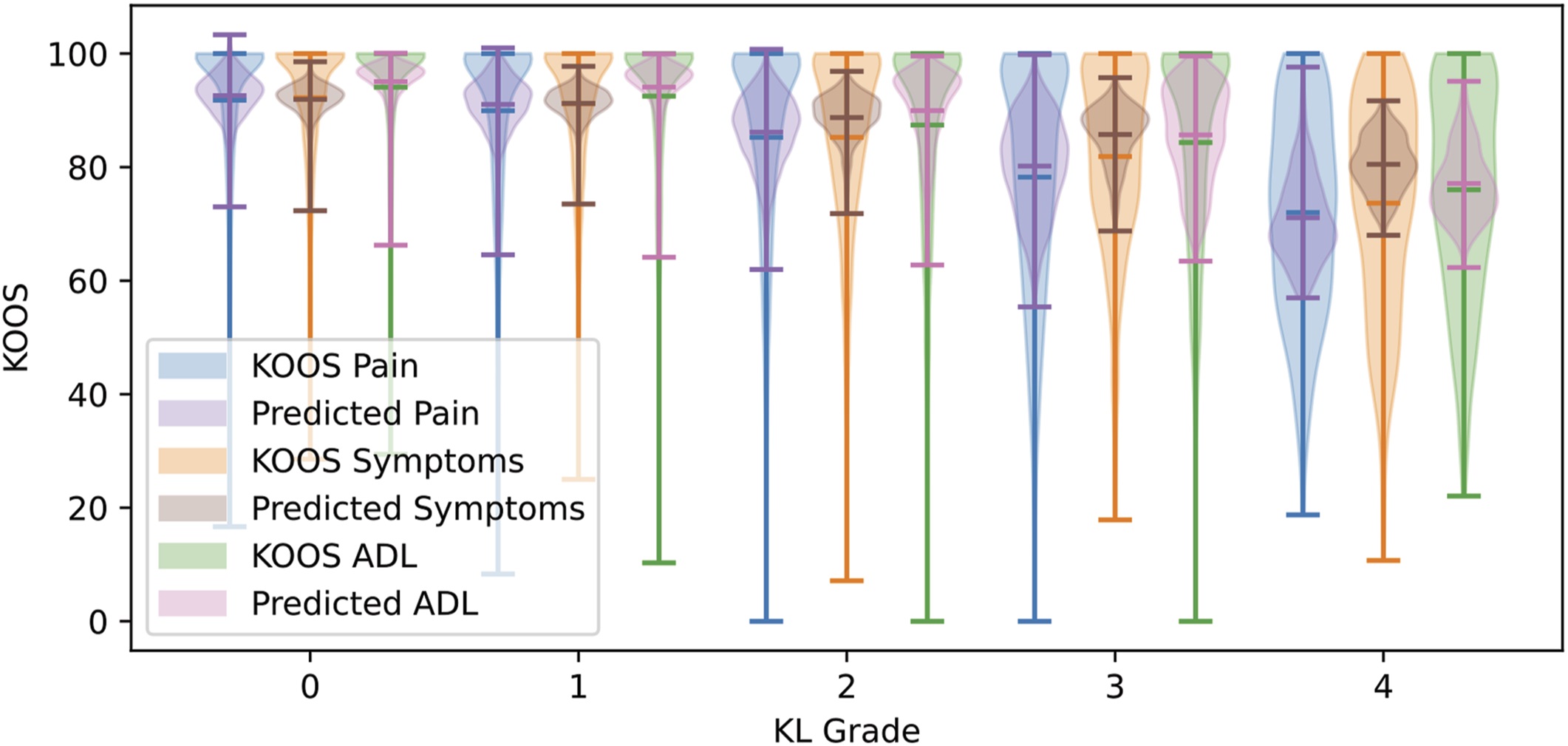

This work evolved from our work in training CNNs to predict pain from bone structure in X-rays. We started eager. What if we give a CNN no preconceptions and just ask it to learn how to predict patient pain just from an X-ray. The result was this paper:

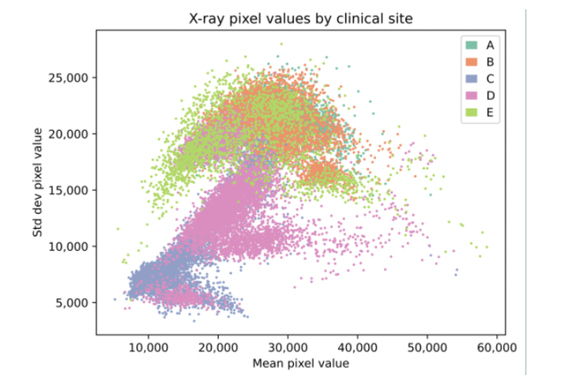

As we continued to work on other projects, we started to get suspicious. Lots of papers are getting similar results. Predicting things in the accuracy range of mid-60%. First, this started with trying to make sure the PHI blackout marks on the X-rays we were using didn’t have an obvious pattern that might indicate where they were from. Then we saw a paper from MIT and Harvard that showed how well CNN could see a patient’s self reported race in an image. If CNNs can see race, then they could use the imbalance between races in the data to “cheat.” But it isn’t just race. What about the X-ray/MRI machine itself? Do different makes and models have detectable signatures? A lot of critical questions arose.

Shortcutting

This work examines the problem of shortcutting when deep learning models are used on medical images for research.

Quite simply, shortcutting is when a DL model makes the right decision but for the wrong reasons.

One of the classic examples came from a model used to identify different animals in pictures. While the model was getting things correct, researchers discovered if a picture showed a cow in a desert, it would guess camel. And if a picture showed a camel in a field, it would guess cow.

This is a known problem. You built the model to solve a task but gave no guidance on how.

This can be a problem in using these techniques for medical research since, on one hand, you want to leverage the fact that the model can learn to see things the human eye cannot. On the other hand, you want the model to use medically relevant clues and not unrelated artifacts in an image.

A common medical example came from research that was examining chest X-rays. They thought the model was doing wonderfully, but really, it was using the fact that sicker patients often had a tube in their throat (and it showed up on the X-ray).

Medical researchers know to look for easy artifacts like this. Our work examines how shortcutting can go far deeper.

On a set of knee X-rays, we found the model was able to learn self-identified patient race and gender, the clinic they went to, and even the year the X-ray was taken. Given all this, when you ask the model to detect something weird like whether a person avoids drinking beer or eating refried beans just from their knee X-rays, you can get much higher accuracy than a 50/50 guess. That doesn’t mean that your preference for beans is really visible in your knee bones. It means it found patterns in the images that it could use to get a more accurate answer than a 50/50 guess. It could be guessing based on a mix of gender, race, the X-ray manufacturer, and even things you didn’t even think to measure.

Even if you prevent it from learning one of these elements, the model will instead learn ones it would have previously ignored. This danger can lead to some really dodgy claims, and researchers need to be aware of how readily this happens when using this technique.

To be clear, this doesn’t discount all DL models. People make mistakes all the time. If a model can be shown to measure something more accurately than humans can or predict a disease more accurately (and with less bias), then it is an advancement in healthcare.

And even more confusing is the fact that sometimes these shortcuts can make a better model. Say a model sees some signs that might indicate the presence of disease. If that disease was more prevalent in one gender, you may want the model to learn to detect gender.

The burden of proof just goes way up when it comes to using models for the discovery of new patterns in medicine. Part of the problem is our own bias. It is incredibly easy to fall into the trap of presuming that the model “sees” the same way we do. In the end, it doesn’t. It is almost like dealing with an alien intelligence. You want to say the model is “cheating,” but that anthropomorphizes the technology. It learned a way to solve the task given to it, but not necessarily how a person would. It doesn’t have logic or reasoning as we typically understand it. These models understand statistical patterns in which things like race, gender, and everything else are blurred together and just patterns in pixels, not independent concepts.

This work has spanned two publications so far:

How obvious are the patterns in images? We look as simple pixel patterns that would be apparent at even basic statistical levels. Each machine has its own statistical signature.

Then we probed more deeply, looking at what CNNs were and weren’t learning. The results shocked us. Somehow the CNN could even make a good guess at what year an X-ray was taken. How?

We’ve released the source code for this work here: